Racing the King by Wrath James White

When I first learned Stephen King wrote several novels under a pseudonym, I was upset. Allow me to explain.

When I first learned Stephen King wrote several novels under a pseudonym, I was upset. Allow me to explain.

Beginning with the very first book I ever read, I developed the habit (or perhaps compulsion is a better word) of picking a subject matter and reading every book written on that subject in the three local libraries I had access to—Lovett Memorial Library, Northwest Regional Library, and the little library at Lingelbach Elementary School. The first subject I latched onto, like many six-year-old boys, was dinosaurs.

My grandmother, Luvader Logan, bought me my very first dinosaur book. I was instantly obsessed. Over the course of that year, I read every book in all three libraries on prehistoric beasts. Then came modern animals, both wild and domesticated, then paranormal phenomena, aliens, and then the Tolkien trilogy. Then I read Firestarter.

Firestarter was the book that began my love affair with the writings of Stephen King. I was eleven or twelve when I first read it back in 1982. I’ve read it seven or eight times since. What fascinated me, captivated me, about that book was it required far less suspension of disbelief than reading about hobbits and trolls. I believed Firestarter. I believed in pyrokinesis and mental domination. I wasn’t suspending my disbelief. Stephen King had actually convinced me these things were possible, at least for the duration of the novel, and that completely awed me. So, my new quest was to read everything Stephen King had ever written.

The problem, however, was that I had a late start, and the good Mr. King was still writing. This was the early eighties, when he was throwing down six thousand words a day and cranking out two to three books a year. But I was on a mission.

I imagined we were in a competition, that he was in on this crazy game with me. I read Cujo and Salem’s Lot. He wrote Christine and Pet Sematary. I read Carrie, The Stand, The Dead Zone, and Cycle of the Werewolf. He wrote The Talisman. I read Christine and Pet Sematary. He wrote It, Misery, and The Tommyknockers. It was a race I was determined to win. I would not be denied.

In one year, I read Night Shift, The Talisman, The Shining, The Dead Zone, Different Seasons, Eyes of The Dragon, and Skeleton Crew. I even convinced my high school English teacher to allow me to read It instead of Julius Caesar because it was “more relevant to my development as a writer in today’s market.”

I was catching him. No one, not even the wildly prolific Mr. Stephen King, could write faster than I could read. And, somewhere between 1987 and 1988, right before graduating from the Philadelphia High School of the Creative and Performing Arts, I caught up. I had read every Stephen King novel written up to that point (with the exception of The Dark Tower), or so I thought. That’s when my then best friend and fellow Creative Writing major told me about “The Bachman Books.”

“The what?”

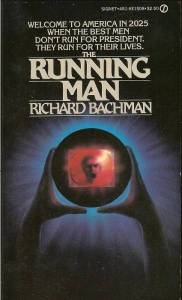

“The Bachman Books? Come on, you know. Stephen King wrote a bunch of books under the pseudonym Richard Bachman. They talked about it in Writer’s Digest a couple years ago.”

“You’ve got to be fucking kidding me!”

What fuckery was this? I had been tricked, fooled, bamboozled! Mr. King hadn’t played fair. I’d read everything he had written to that point, even the new stuff, while keeping up with my school work and all my other reading and writing assignments. Even as his books grew longer and longer, I’d still managed to read them all. But he had been slipping books past me the entire time. I was pissed. Unreasonably so. But I wasn’t ready to give up. So, I read Rage, Roadwork, The Long Walk, Thinner, and finally, The Running Man.

The Bachman novels were noticeably different. They were bleaker. The heroes weren’t terribly heroic. Ben Richards, for example, was kind of racist, sexist, and homophobic. The n-word fell from his lips too effortlessly, as did “faggot” and other unflattering terms. Yet, I knew guys like him. Uncivilized, crude, anti-authoritarian, yet intelligent and possessed of a bravery born of hopelessness and desperation. And we were all a little racist, sexist, and homophobic back then. They were less enlightened times. I look back on some of the ideas and opinions I held in the 80s and cringe. Ben Richards wasn’t a great guy, but I could relate to him. He was from the streets, just like me.

I grew up in a part of Philadelphia that guys who looked like Stephen King couldn’t walk safely through at night. Yet, I was betting on my ability to tell a scary story to get me out. My odds weren’t terribly better than Ben Richards’s odds of avoiding the hunters for 30 days.

The cops in my neighborhood were as brutal and corrupt as those chasing Ben Richards. You could bribe a Philly cop out of a traffic ticket with five bucks back in the 80s, and everyone knew you got the best weed from cops. They would take it from white college kids, let them off with a warning, and sell it back to us. You wanted an untraceable firearm? Buy it from a cop. That’s what Philly was like in the 80s. Those of us who knew how to navigate all that corruption and criminality did okay. Others? Not so much.

The folks who lived in the more affluent neighborhoods like Mount Airy and Chestnut Hill were as oblivious and indifferent to how the rest of us lived as Amelia Williams was to the lives of the contestants on The Running Man, plucked from the slums to die for the amusement of the well-to-do while maintaining the facade that they had a fair chance.

Just like the wonderful folks who reply “All Lives Matter” as a way to silence those proclaiming the equal value of Black American lives, Amelia and her ilk fervently believed the contestants they saw slaughtered on the “Free-Vee” were hardened criminals, anarchists, and murderers rather than poor people trying to scrape out a living any way they could, reduced to bartering their lives for the lives of their families. They believed the underclass were all animals who would have come for their posh insulated lives, destroyed their entire way of life, raped their women, and murdered their kids had they not been stopped. Their deaths were justified by how and where they lived.

The poor are dangerous. This wasn’t just an idea manufactured by Mr. King to give his novel more drama. This is how the upper class always looked upon us on the bottom. We were dangerous, subhuman, savages, impossible to empathize with, unworthy of sympathy. If we only worked harder, we wouldn’t be in the situations we were in. In their eyes, our poverty was proof of our laziness and poor character. The same dehumanization that allowed the upper-class citizens of King’s dystopian future to watch poor people murdered for sport is what has allowed that same class of people to watch people of color in this country murdered by police while justifying and excusing it.

“He shouldn’t have run.”

“He shouldn’t have resisted.”

“She shouldn’t have talked back.”

“She should have followed the officer’s instructions quicker.”

“He must have been doing something wrong, or he wouldn’t have been stopped.”

Over the years, King’s vision of 2028 has come to me again and again in sudden bursts of déjà vu as reality shows like Cops, America’s Most Wanted, and even The Ultimate Fighting Championships hit the airwaves. When I was twenty-four, awaiting the birth of my first child while working as a bouncer at a nightclub, I watched the very first UFC and began training to enter it. I fought in No-Holds-Barred tournaments all over The Bay Area for a few hundred dollars to buy food and clothing for my wife and son.

When the economy imploded in 2009 and I lost my ninety-thousand-dollar-a-year job as a construction manager, I considered coming out of retirement, at forty years of age, and taking a few fights just to put food on the table. I was older, slower, with joints that ached with arthritis and injury from all the abuse I had put my body through in the ring and the cage, but I was ready to risk my life to feed my family. I knew exactly how Ben Richards must have felt.

Luckily, it didn’t come to that. I sold a few manuscripts instead. But who knows what may have happened if no one purchased my novels. If the country was ruled by an omnipotent TV network, and the only way to take care of my family was to enter contests like “Treadmill to Bucks,” “Swim The Crocodiles,” “Run For Your Guns,” or “The Running Man.” See, the wonderful thing about Stephen King’s writing, just as I’d discovered almost forty years prior when I was an eleven-year-old kid reading Firestarter for the first time, was that it didn’t require much suspension of disbelief to imagine myself making the choices Ben Richards made. I was convinced I would do it. Given the choice between letting my family starve or running from an entire country eager to kill me, for a slim chance at a better life for my loved ones, I would have gone out the same way Ben Richards did, grinning and giving the establishment the finger.

Oh, and if you’re wondering if I ever caught up, if I ever managed to read everything Stephen King has ever written, I didn’t. But the game isn’t over.

The complete list of the books to be read can be found on the Stephen King Books In Chronological Order For Stephen King Revisited Reading Lists page. To be notified of new posts and updates via email, please sign-up using the box on the right side or the bottom of this site.

WRATH JAMES WHITE is a former World Class Heavyweight Kickboxer, a professional Kickboxing and Mixed Martial Arts trainer, distance runner, performance artist, and former street brawler, who is now known for creating some of the most disturbing works of fiction in print.

Wrath is the author of such extreme horror classics as THE RESURRECTIONIST (now a major motion picture titled “Come Back To Me”) SUCCULENT PREY, and its sequel PREY DRIVE, HORRIBLE GODS, YACCUB’S CURSE, 400 DAYS OF OPPRESSION, SACRIFICE, VORACIOUS, TO THE DEATH, THE REAPER, SKINZZ, EVERYONE DIES FAMOUS IN A SMALL TOWN, THE BOOK OF A THOUSAND SINS, HIS PAIN, POPULATION ZERO and many others. He is the co-author of TERATOLOGIST co-written with the king of extreme horror, Edward Lee, SOMETHING TERRIBLE co-written with his son Sultan Z. White, ORGY OF SOULS co-written with Maurice Broaddus, HERO and THE KILLINGS both co-written with J.F. Gonzalez, POISONING EROS co-written with Monica J. O’Rourke, among others.

“

“

When I was a teenager, I spent several summer vacations working a government job at nearby Aberdeen Proving Grounds and Edgewood Arsenal. My duties ranged from laying asphalt to landscaping to pulling up old railroad tracks to shredding government documents.

When I was a teenager, I spent several summer vacations working a government job at nearby Aberdeen Proving Grounds and Edgewood Arsenal. My duties ranged from laying asphalt to landscaping to pulling up old railroad tracks to shredding government documents. I couldn’t wait to read the Bachman books. By that time I was rereading the early Stephen King bestsellers simply because I needed a fix. I am of the age when realistic fiction was the standard form of the masters. In my top ten of novels is In Dubious Battle by John Steinbeck. And the first trilogy I ever read was Studs Lonigan by James T. Farrell. Proletarian fiction if you will.

I couldn’t wait to read the Bachman books. By that time I was rereading the early Stephen King bestsellers simply because I needed a fix. I am of the age when realistic fiction was the standard form of the masters. In my top ten of novels is In Dubious Battle by John Steinbeck. And the first trilogy I ever read was Studs Lonigan by James T. Farrell. Proletarian fiction if you will.